- Home

- Simon West-Bulford

The Soul Consortium Page 2

The Soul Consortium Read online

Page 2

“That’s because no aberrations existed before you entered the last life.”

I look around, wishing for the thousandth time there was a face to the voice that spoke to me. Then I realize the significance of what she said. “How can there suddenly be aberrations? What are they?”

“I began inspecting the algorithms used by the Calibration Sphere while you were in the WOOM. The Codex protocols don’t allow me to examine the souls themselves, but I saw ways in which to improve the calibration checks, just to make sure routine maintenance wasn’t missing any discrepancies within the soul recording. It seems I was right—”

“You were checking the checkers?” I smile despite myself. “Could the mighty Qod actually be … bored?”

“—because during the third universal cycle, inconsistencies, some greater than others, have emerged in the patterns of many souls.” There is no humor in her voice this time.

I wait a moment, hoping she will elaborate, but she doesn’t. “Inconsistencies? Explain. Is it data corruption or degradation?”

“No.”

“Then what?”

No reply.

“You don’t know? Seriously?”

“Analysis is incomplete. And as I said, the Codex protocols don’t allow me to examine the data myself. If you—”

“I want to go there.”

“My analysis is incomplete. The aberrations might be dangerous, Salem. Please reconsider.”

All at once, as the thought of danger—real danger—presents itself, I feel a chill of excitement. Until now I have drifted from life to life, walking through the memories of multitudes, knowing deep down I was safe, my psyche buried within, saying, “It will never happen to me.” But this will be different. “I said I want to go there.”

“Very well. Would you like to walk?”

“Yes, and can you brief me on the lives with the ten most significant aberrations as we go? I used to like the surprise in the Bliss Sphere, but I’d prefer to know what I’m getting into with these.”

“Processing.”

THREE

The new sphere opens before me. It looks much like the Bliss Sphere, but instead of the soothing pulse of aquamarine, a naked glare, like a nova shining through emerald glass, bathes me as I step inside. I shield my eyes until they adjust. The smooth walls glitter like the inside of a geode; each glint of light is the electron pulse of a human ghost waiting to tell me their story, and I survey them, wondering which of these I would become intimately familiar with in the next few minutes.

“Have you made your choice, Salem?”

Qod gave me the summaries by the time I reached the sphere, but I already made up my mind before she reached number five. “Yes. Select subject 5.64983E+30, Orson Roth.”

“Interesting. Why him?”

“Anyone with an obsession that powerful must surely see something there that I haven’t, don’t you think?”

“Not really.”

“Well, I have to start somewhere,” I say, stepping through the oval door. “And I want to look inside people nobody else would ever consider. Remember the others?” I twirl my hand in explanation. “They were searching for the answer in all the obvious people—Jesus Christ, Albert Einstein, Nietzsche, Shaphad Seth, theologians, scientists, visionaries, and philosophers through all history. And what did they find, hmm? Nothing! But I will.”

“In men like this?”

“As I said, it’s a start. I’ve made my choice.”

Subject 5.64983E+30: Select.

Subject 5.64983E+30: Aberration detected.

Subject 5.64983E+30: Override authorized—ID Salem Ben.

Subject 5.64983E+30: Activate. Immersion commences in three minutes.

The smell of freshly cycled oxygen perfumed with summer jasmine fills my nostrils as the sphere welcomes me, but I sense disapproval in Qod’s silence that nullifies its pleasure. She rarely stays quiet for long, though. The loneliness would be unbearable if she did.

“Need I remind you,” she lectures me, “that once you have been immersed you will not be able to withdraw until the moment of the subject’s death. Protocol forces me to dictate that whatever you experience, however terrible, you will have to endure it without possibility of extraction. You will know each and every moment as if it were your own, and until it’s over, you will have no suspicion at all that you are not that person. Any lasting memory of trauma …”

Qod’s redundant legal chatter echoes in my peripheral thoughts as I wait. Ironic that I should feel such impatience after being alive so long. Of course there is no need for her to remind me. Doesn’t she know how many lives I’ve lived? Does she somehow forget that the extended human brain can retain and recall any moment from the past with instant and precise clarity? Perhaps I do need reminding, though. I have never known of an aberration before today; I have no idea what could be waiting for me once I enter the recorded life of Orson Roth. The thought prompts another ripple of enticing fear across my skin—better this than going back to the Bliss Sphere.

“What’s the worst that can happen?” I smile. “Plug me in.”

“Remember. I warned you.”

“I’m incapable of forgetting, or don’t you remember?” I reply flatly.

“What I remember is that there are some things you choose to forget. If this goes wrong, I’ll make sure this isn’t one of them.”

Suspended twenty feet above by invisible fields of force, the machine waits for me like the shiny wet cocoon of an enormous insect. The wheeze of miniature hydraulics and the hiss of ancient gravity valves echo around the sphere as the machine makes its preparations for my long stay, but to me it sounds like Qod is sighing with resignation over my decision.

A flow of silver glides down to me from the curved walls, microscopically thin fibers carrying me gently upward to the center of the sphere, as if my timeless companion were gathering me up in her hair to hold me against her breast. The tiny fibers dig through my flesh, penetrating my nerves, weaving through the hills and valleys of my brain as I am pulled into the WOOM. Energized with a new sense of adventure, I ponder a moment on who eliminated the human body’s need for pain, replacing it with a simple internal alarm mechanism. But pain is undoubtedly a sensation I will be reacquainted with in the next few minutes as I emerge wet and gasping from between the thighs of my new mother.

A bright spot of life ejects from one of the millions of storage cells layered into the wall opposite me. It drifts in the air like a fairy caught in the breeze, then fires into the machine.

“Farewell, Salem. See you in forty-six years.”

ORSON ROTH

As I was walking up the stair

I met a man who wasn’t there.

He wasn’t there again today.

I wish, I wish he’d go away.

ONE

Fate must be the strangest among the gods. She manipulates the world with immutable will—so devious and cunning yet she stands aloof from her pawns, unwilling to flaunt her talents. To recognize her one must have a very special mind indeed. And to appreciate her? Well, one must be insane.

Of course, there are times during her most fickle moments when she will show herself plainly, but they are rare. Take the advancement of science as an example. Galileo Galilei, desperate to usher mankind into a new era, determined to topple Ptolemy’s convenient model of the Earth at the center of the heavens with the sun circling us, and yes, where Copernicus tried before him and failed, Galileo—he succeeded.

Was that supposed to be the end of his victories? Of course not! How do I know? The answer is Fate. She intercepted this world with such obvious intent to finish his work. Galileo, you see, had wonderful ideas taking form in that incredible mind of his, but Death, as is his way, wanted the last word. He stole Galileo from us before he could bear fruit. But our goddess, in a rare moment of weakness or passion, revealed herself. Many had not seen it, but some of us now do. On the day Galileo Galilei died in January 1642, the fruit that had been pruned from

his branch took seed elsewhere, and a little over nine months later, Sir Isaac Newton was born to continue the work Galileo had been denied.

You may believe this to be coincidence or mere trivia, but I know different, for Fate played the same game with me too. In the same minute that Zachary Cox succumbed to violent death, my mother gave birth to me, and my entire life has been a continuation of that man’s work. Zachary Cox had already murdered fifteen people in the six years before his career ended at my parents’ house. Naturally, I have no firm memory of that day, but I am well versed with the most dramatic recitation of the story, and sometimes I think I can hear my mother’s dying curse when I close my eyes to sleep.

My parents, Jack and Evelyn Roth, lived their quiet lives in a village in the north of England, enjoying a time of nervous peace after the Second World War. They intruded upon no one, worked hard for their neighbors, and were loved by the whole community, small though it was. My father earned their keep as a carpenter, lovingly carving rocking horses from the oak trees grown in the local woods; my mother painted them and sold flowers for the church. I should have been born into a family of warm roses and gentle prayer. But Fate had her cold eye fixed on my mother’s womb. She rescued me from that sickly sweet life.

August 17, 1951, changed everything for that village. It was late evening, a street party had finished outside my parents’ cottage, and the hearty enthusiasm of villagers with satisfied bellies full of wine and hog roast spilled over into song as they sauntered back to their homes. They knew my mother was due any day, and when she and my father had not arrived for the celebrations, it was assumed the big day had finally arrived and Dr. Maidestone would be overseeing the joyous event. Community spirit was high in those days but obviously not high enough for the locals to overcome their convenient ignorance of the violent screams coming from the Roth household that night.

Perhaps it was because the atmosphere in the village was one of such contentment or because the pink glow of the sunset lulled everyone into dreamy complacency, but not one resident entertained the possibility that the formidable Zachary Cox would be paying a visit to one of their homes that night. Why would they? Village life was better now that the war was forgotten—safe, quiet. It was time to bury the heartache of the past along with their loved ones and start appreciating better days. Nobody wanted to think about blood and horror anymore, let alone talk of such things. The murders they’d read in the papers were for other places. Not this village.

Dr. Maidestone had been sitting with my mother for most of the afternoon, holding one hand whilst my father held the other, both smiling and breathing words of encouragement. An ambulance was called when complications arose after her water broke, but because the streets had been closed to traffic, the driver took a different route through the back lanes and crashed at a tight bend; help never came. By the time the news came back to the Roths, my mother decided that Fate had granted her wish to give birth at home. She told the doctor it was what she wanted anyway. But had I been there to explain to her this error of judgement, I would have told her that this was Fate’s warning, not a blessing: my birth and life would be surrounded by untimely death.

Mr. Cox crawled in through the open window of the pantry when the contractions reached four-minute intervals. He was not expecting anyone to be home, and in truth, it is my belief that he had already begun to turn over a new leaf. I don’t believe he wanted to kill my parents or the doctor, but Fate obviously did.

In my teenage years I learned that Cox’s antisocial condition was brought on by the fact that he had been a conscientious objector to the war for religious reasons. The guilt of his survival and the death of his friends had manifested into a form of bloodlust executed with supreme efficiency and wondrous design, a skill I have since come to deeply admire. When the war ended, so did the murders. Nobody found him out, but as mental instability grew, so did the list of jobs ending in his dismissal, and Cox was forced to join the ranks of those who made their living through theft. Cox had chosen our village that night because of the street party, and I can only assume that the Roth home was chosen because Fate shined her irresistible ghost light upon it. Cox would end, and I would begin.

It was my father who heard the noise first. Expecting it to be an overenthusiastic celebrator, he reassured my mother that he would be gone less than a minute. She screamed her disapproval as he pried her sweaty fingers from his hand, knowing that my moment was coming, but he went anyway. The chaos and bloodshed that followed was regurgitated by the tabloids and spoken by grimacing mouths for years afterwards.

The whole scene played out in less than five minutes. Cox and my father crashed out of the pantry, across the landing, and into the living room like impassioned dancers, Cox clutching my father’s hair, my father’s strong carpenter arms wrapped around the murderer’s chest. Grunts escalated to screams as hair ripped from my father’s scalp; crockery displayed on the mantelpiece shattered as it met the tiles on the fireplace, and both men fell, thrashing against each other amongst shards of broken china. Cox cried out as one of his fingers snapped.

Maidestone shot looks of desperation between the fighters and my distraught mother as the violence came closer to her. Gripping her hand harder than she gripped his, blood pooling in the shallow birthing water, Maidestone shouted for both men to stop, but as the conflict reached its peak, only one did—my father.

He gurgled with the effort of movement, trembling fingers splayed over his stomach as blood spread across his shirt like ink on blotting paper. Cox struggled up as the victor, coughing and breathing heavily, and stared at the doctor and his patient with a bloodied screwdriver in his right hand and the look of a wounded wolf in his eyes.

Before the doctor had a chance to react, fire belched from the fireplace. In his last effort, my father drew the poker from the coal to slice Cox’s cheek with a wild swing. The murderer roared, but the attack only fuelled his rage, and with triumph proclaimed in his cry, he stamped his boot repeatedly into my father’s face. The clang of the poker released by the twitching hand followed the sickening crunch of bone against gristle and brain.

Only then did Dr. Maidestone, transfixed by the horror, make his move. He leapt forward to tackle Cox, and the two of them wrestled in the soot, blood, and fire, while my mother screamed a new life into the world, my own cry joining the crescendo.

Both men paused as the birth reached its climax. My mother pushed herself backward, slipping and splashing, wailing at the sight of her dead husband.

Maidestone grabbed Cox’s injured hand, yanking the broken finger, then twisting the arm so he could thrust him into the fire. Spikes from the fireguard pierced Cox’s back, and he arched with the pain as the doctor stumbled toward my mother, hoping his action was enough to stop their attacker. It wasn’t. Cox crawled away from the fireplace with flames leaping over his sweater to blister his face. Maidestone did his best to pull me free from my flailing mother, but Cox had already reached him and plunged the screwdriver into the doctor’s spine, stabbing with what little energy he had left.

“Please” was the last thing the doctor said before Cox thrust the screwdriver into the man’s throat when he turned.

Cox fell forward onto the wet floor and pointed at me as I lay there taking my first few breaths of life. My mother stopped moving and crying, and as the sound of splintering wood signaled the entry of my rescuers, my baby-blurred vision captured the last moment of life ebb from Cox’s eyes. My first memory.

TWO

Life between my first memory and my first murder blurred together like a hideous mosaic assembled by some lunatic using pieces of his own hardened vomit. Predictably, it was ugly.

The first few chunks of that depraved picture were set in place when I reached my fourth year. My foster parents, ever joking to their friends about my tempestuous nature, did not have the intuition to predict what I would do when left unsupervised in a playroom with the neighbors’ baby. It was only for five minutes, they reasoned, but for th

ree of those minutes Donovan stared at me. Smiling and drooling, with no idea that Fate was about to use him as my first training exercise, the infant, two years my junior, tap, tap, tapped his rattle against his podgy thigh, hypnotizing me with his baby blues. I wanted to see how they worked. So I took them. Or tried.

I don’t know what became of baby Donovan after my distraught foster mother tore my bloody fingers away from him. I never saw her again after that day.

Finding new parents was almost impossible after that, but between seasons at various children’s homes, I occasionally passed to new guardians under increasingly strict regulations. But the harder they pressed upon my will, the more I pushed back, and knowing that my goddess had reserved a special place for me in her heart, I drove social workers and child psychologists to near insanity with every new incident. I don’t regret a single moment of those years. Fate forged me for the passions to come.

At the age of ten, they inflicted me upon the children’s division of Kettlewhite Mental Institution. And it was only in there, amongst the truly insane who had no life in their eyes, that I realized I had to tame my urges if I wanted to serve Fate properly. I wept convincing tears of remorse after each violent episode, performed well in group activities, and responded properly to the Rorschach tests—a butterfly instead of a torn throat, a flower instead of a cudgeled head—until I seeped into their favor and gained their trust. They released me back into the wild to new parents and to grammar school. I sat at the rear of the class, absorbing the insults and isolation, a tamed wolf circling the sheep, waiting for Fate to point out the strays from the flock.

I remember my first killing as though the images had been tattooed on the inside of my eyelids. At sixteen, learning to fulfil my calling as an outcast, I spent as much time alone as I could, and on that particular day, I decided to pay a visit to the banks of the stagnant pond in the woods near my school. I liked to go there before returning home; it was a good place for contemplation—a metaphor for my mind. I loved to stare at the green scum that covered the surface, thinking about how so many people had no idea what lay beneath the murky depths of the child they thought they knew.

Dark Seed

Dark Seed The Soul Continuum

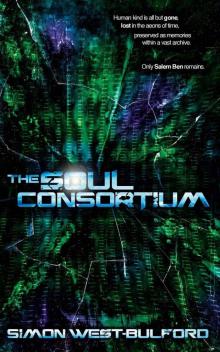

The Soul Continuum The Soul Consortium

The Soul Consortium The Beasts of Upton Puddle

The Beasts of Upton Puddle